BIKO, Let the Lions Teach!: Literacy, Intention, and the Power of Authorship

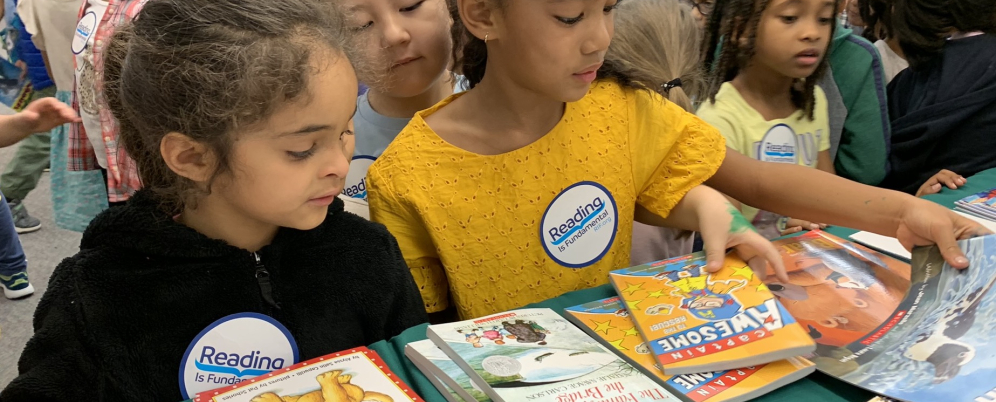

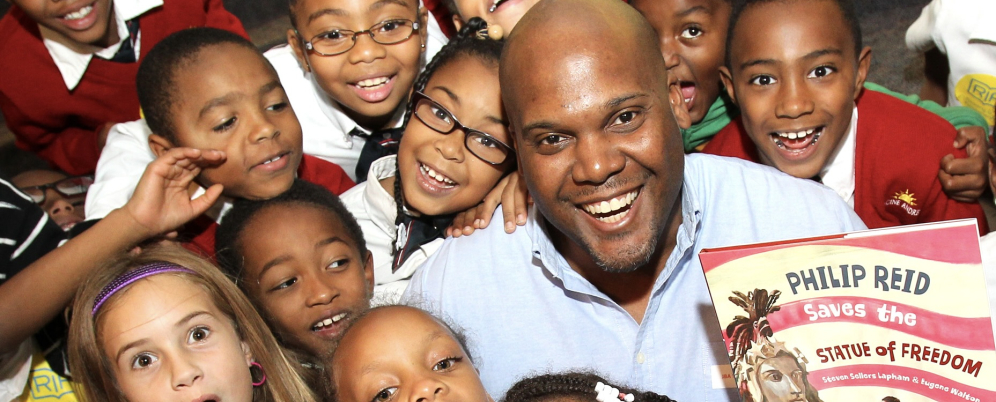

Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) embraces a culturally relevant approach to literacy education. Culturally responsive literacy is a powerful way to motivate young readers because it helps children see themselves, their families, and their lived experiences reflected with care and authenticity on the page. When books move beyond surface-level representation and honor culture, history, and voice, reading becomes more than a skill, it becomes a source of connection, confidence, and belonging. RIF believes that all families have rich social and cultural literacy practices and research shows that educators who tap into the cultural and historical knowledge and competencies of households improve relationships with families and enhance their literacy curriculum. In this guest blog, Dr. Nneka Gigi-Patton (Dr. Gigi), a PhD-trained educator, literacy strategist, and cultural practitioner, explores how intentional authorship and culturally grounded storytelling can transform how children engage with reading. As a partner of RIF, Dr. Gigi brings her research, community-based work, and creative literacy projects together to show how empowering young readers starts with honoring who they already are.

“Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”

— Chinua Achebe

Achebe’s words are often quoted in conversations about representation, but their demand is far deeper than visibility. He is not calling for more stories about the lion or its hunter—he is calling for authorship, authority, and intention. Who tells the story matters. Why the story is told matters. And what the story teaches a child about themselves and their world matters.

In today’s literacy landscape, we are seeing more children’s books with Black faces on the cover. More Afros. More “diverse” illustrations. While this shift is important, culturally responsive literacy cannot stop at appearance. When representation lacks cultural grounding, historical context, and intentional authorship, it risks becoming performative—decorative rather than transformative.

What Intentional Literacy Looks Like on the Page

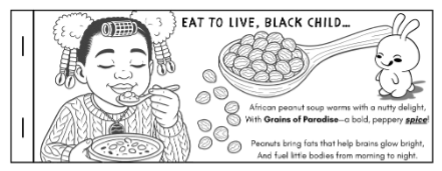

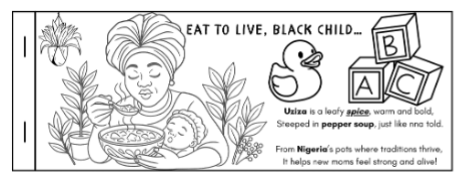

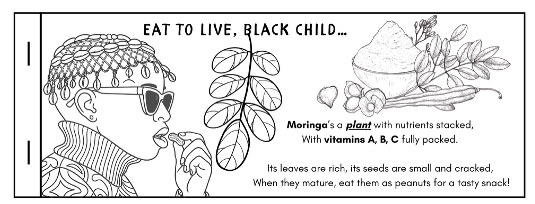

The pages from Eat To Live, Black Child and Afro-Mation included throughout this piece offer a different model—one rooted in cultural memory, lived practice, and care.

In Eat To Live, Black Child, the illustrations do more than introduce food—they tell layered stories:

- One page centers a child savoring African peanut soup, connecting nourishment to warmth, family, and ancestral kitchens. The text does not exoticize the dish; it situates it as knowledge passed down, affirming that cultural foods are sites of intelligence and wellness.

- Another page shows a mother feeding her baby pepper soup infused with uziza, explicitly naming Nigeria and postpartum care. This is not generic “African culture”—it is specific, relational, and intentional. Literacy here becomes a bridge between literacy and an ongoing Black infant and maternal health crisis.

- A third page highlights moringa as a plant with healing properties, pairing botanical knowledge with playful rhyme and visual clarity. Children are invited to learn science, language, and cultural wisdom simultaneously—without flattening any of them.

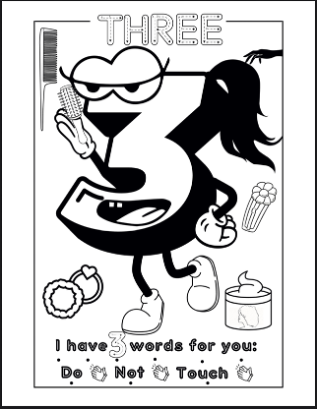

Similarly, the Afro-Mation coloring book pages resist the idea that affirmation must be shallow or abstract:

- One page personifies a letter as joyful, confident, and expressive—linking phonics to identity, movement, and self-belief.

- Another page pairs tracing, affirmation, and culturally familiar imagery, reinforcing that learning letters and loving oneself are not separate acts.

Across both projects, culture is not an add-on. It is the curriculum.

Moving From Performative to Purposeful

This distinction echoes the work of Paulo Freire, who taught that education is never neutral. Literacy either reinforces dominant narratives or helps learners name their world and themselves within it. Intention is what separates the two.

In my work installing Little Free Libraries in book deserts and facilitating Beyond Adornment Club gatherings, I see the difference immediately. When children encounter books that carry cultural specificity—food they recognize, hairstyles with meaning, languages and rhythms that feel like home—they don’t just read. They respond. They connect. They claim ownership.

This is culturally responsive literacy in practice: not savior-driven, not deficit-based, and not centered on what children supposedly lack—but on what they already know.

Questions That Keep Us Honest

For authors and illustrators:

- Have I researched the rituals, meanings, and histories behind the African hairstyles I depict?

- Do I understand the origins of the textiles, foods, or symbols I include—or am I using them as aesthetic shortcuts?

- Am I centering the child’s voice and agency, or writing from an outsider’s gaze?

For parents, caregivers, and homeschoolers:

- What does this book teach my child about who they are and where they come from?

- Is culture shown as living and specific—or vague and decorative?

- Does this text invite pride, curiosity, and conversation?

These questions are not barriers to creativity. They are invitations to integrity.

An Invitation to Build Together

If this vision of literacy resonates with you, I invite you to continue the conversation beyond the page.

Join the Beyond Adornment Club private Facebook group—a nurturing space for African, Caribbean, and Afro-Latino girls from birth through grade 6, along with the caregivers, educators, and community members who support them. It is a space rooted in literacy, hair, culture, and joy—where learning is embodied and collective.

You can also order custom culturally responsive literacy materials or request bespoke tools for your home, classroom, or community space through my consulting site. Whether it’s curriculum, coloring books, or culturally grounded learning experiences, the goal remains the same: to ensure our children are not just represented—but understood, affirmed, and empowered.

Because when lions author their own stories..literacy becomes liberation. Daalu.

Dr. Nneka Gigi-Patton is a PhD-trained educator, literacy strategist, and cultural practitioner whose work centers culturally responsive literacy, Black girlhood, and intergenerational learning. She is the founder of Beyond Adornment Club and a Little Free Library steward, designing literacy experiences that honor African and diasporic traditions through story, food, hair, and ritual. Her work bridges research, community practice, and creative design to support children from birth through elementary school in seeing themselves as knowledge holders and storytellers.

Project Blurb

Eat To Live, Black Child and Afro-Mation are culturally grounded literacy projects created to move beyond surface-level representation and toward intentional, affirming learning. Through Afrocentric imagery, ancestral foodways, phonics, and affirmation, these materials invite children to explore language, identity, and cultural knowledge simultaneously. Designed for homes, classrooms, and community spaces, the projects reflect a commitment to literacy as care—rooted in history, joy, and lived experience rather than performative inclusion.

Get Inspired—Read RIF's Blog

Stay connected with the heart of our mission by exploring our blog. We feature stories from communities we serve, literacy tips for educators and families, and updates on how Reading Is Fundamental is helping children across the nation discover the joy of reading.